I’ve been charged by police on horseback while protesting government inaction on AIDS. In September 1991, President George H. W. Bush visited Philadelphia, and the street in front of the hotel he was in was filled for the entire block with various protesters, including members of ACT-UP. There are competing versions of how a barricade was pushed or fell over, but the police response was quick and violent. I was not near the barricades nor involved with ACT-UP, but mounted police moved throughout the crowd. It was terrifying. Horses are big.

Rebuilding a relationship with my father

I’ve experienced the rewards of rebuilding a relationship with my father. It was an ongoing process over the course of 30 years, and it certainly had its difficult moments, but I can’t imagine what I would feel like now (two years after my father’s death) had we not reconciled.

After his near-fatal accident in 1987, when I called home I would always spend a little time on the phone with my father, usually talking about totally incidental things like the weather. (Or his health, a recurrent theme with first his recovery from his accident, later a heart attack and bypass surgery, and then congestive heart failure and general old age.) Slowly we simply normalized having conversations (although I still got almost all family news through my mother).

One setback was when my sister got married. She invited my partner Paul and I, but my parents pressured her to disinvite Paul. I didn’t go to her wedding. (My family plays hardball.) Not too long later, there was a Sutton family reunion—all the descendants of my father’s parents. At this gathering, out of a couple of dozen people who went, there would be exactly three people named Sutton: my father, my mother (through marriage), and me. (My sister took her husband’s surname.) Here, if anywhere, was a place that bringing my partner would not take the attention off of someone whose day it was.

Meeting an actual person, instead of who knows what abstract things my parents imagined at the fact that I was gay, seemingly made a big difference. My parents came to Philadelphia to visit. While there was no question of their staying in our home, they had dinner in our home and Paul was included in outings without any fuss.

After Paul and I broke up, two other boyfriends visited California with me. The first time my mother preemptively made motel reservations for us, and said she never allowed my sister and her fiance to share a bed, even though she knew they were sleeping together. So it was, at least, equal treatment. On each visit we also visited my sister, and she would put us in the same room. When Bob and I went out to meet my newborn nephew, we not only shared a room at my sister’s house, we were under the same roof as my parents—albeit in an in-law apartment at the other end of the house!

One of the moments that stands out with personal meaning is when I flew to San Diego right after my father’s heart attack and bypass surgery. He wanted to get out of bed (they get you up *right away*), and was insistent that I be the one to help him up. In the largely nonverbal, unexpressive context of our relationship, that meant a lot to me.

On some visit home, I remember driving him somewhere in his truck, and he said he just hoped that I would have a happy life. That’s the moment at which I felt that we were reconciled. Because of his ill health, for a good 15 years, I treated every time I said goodbye to him as though it might be the last time. It was important to feel that we were good when I drove off.

The last time I saw my father, it was between hospital visits for him, and it was an extravagant whirlwind for me. I flew on a very early morning flight to San Diego, rented a car, and drove to a cousin’s house for a pool party. My sister brought my father to the party, as hopefully planned in spite of hospital visits, but he didn’t know I would be there. It was a delight to surprise him. That evening I drove back to San Diego, stayed overnight, and flew home the next day. It was a good visit. As my father declined over the next few months, I was ready to fly home if my sister needed support, but my father and I were clear that we’d said our sufficient goodbyes.

My father wouldn’t speak to me

I spent a year or so when my father wouldn’t speak to me.

I realized I was gay in the late fall of 1978. I told my mother I was gay in the winter of 1979, and she told me not to tell my father (who was paying my way through college).

In 1985 I moved to Philadelphia. I didn’t much like it at first, which I told my mother, but I met someone I decided to move in with (my first live-in partner). When I told my mother I was staying in Philadelphia in order to live with Joseph, that was what finally broke her years-long silence. (She had told no one in all those years.) She told my father, and he was unwilling to speak to me. (Unlike my mother, however, he immediately talked to his cousin Milo about it.) If I called and he answered the phone, he would pass it to my mother. My mother stopped calling because she didn’t want him to see my number on the bill.

In 1987, my father was working on a cotton-picker, which was up on blocks, and it fell on him. It fractured his skull, broke his pelvis and at least one of his legs, and caused some internal damage. He was very lucky not to die. There was a massive blood drive in my hometown for him.

Very early in his recovery, he said that as the cotton-picker fell on him he realized (had a revelation?) that being a family was more important than my sexuality. It was the phone call when my mother told me that he had said this which prompted me to sit down suddenly at work and start crying, and my coworker Ruth to seemingly jump over her desk to come stand by me.

Attacked on the street

I’ve been attacked on the street on my way home from a bar with my lover. It was in Philadelphia in the late eighties or early nineties, and we were crossing Broad Street (in the crosswalk, with the light). When a car full of guys pulled into the crosswalk, Paul turned and pointed at the lines on the street. They reacted by jumping out of the car and beating us.

It happened so fast I don’t really remember what went down (besides me, to the pavement, with some kicking involved). My glasses were broken. We took a cab (I remember saying that I was bleeding but that I was not going to bleed on his car) to an emergency room, where I got some stitches in my eyebrow and an x‑ray revealed a hairline fracture in my nose. (I remember flirting with the nurse.) I had rather spectacular bruises for a while. (I’ve had pierced ears for ever, and had a pierced nipple for a while, and have pierced my nose twice, but the idea of piercing my eyebrow still gives me the heebie-jeebies.)

A bystander got the license of the car, and a police officer took a report while we were still at the hospital. The police eventually said the registered owner wasn’t driving the car, so there wasn’t anything they could do. (The police in Philadelphia were notoriously corrupt and insular, so I suspected homophobia and/or ethnic or extended family solidarity.) One of my coworkers, however, had a son in the police and offered to have someone make inquiries and rough someone up. I declined with a good bit of embarrassed affection.

A disagreement between private school administrators and ill-informed parents.

I’ve been the occasion for a disagreement between private school administrators and ill-informed parents. Some background information about Quakers will make a couple of nuances to the story clearer. (This is a long post, and it’s not really all that exciting of a story. Lots of pedantry about Quakers and a little story at the end. You’ve been warned.)

First, Quakers, for a big chunk of their history between the first flush of enthusiasm (and evangelism) in the 17th century and the early 20th century, developed practices to separate themselves from “the world.” This was sometimes referred to as a hedge, and it played out in a number of ways: endogamy (only marrying within the faith); disownment (public statement that someone was not a member) for infractions of the discipline; criticism of involvement in antislavery or suffrage movements with non-Quakers.

And pertinent to this story, the creation of schools for Quaker children, in order to give them a “guarded” education. There are still many, many Friends schools in operation, from preschool to college. (There were also schools founded by Quakers for other purposes, such as educating formerly enslaved people or as part of missionary foundations.) The vast majority of students in these schools (at all levels) are not Quakers.

Second, traditional Quaker worship (what most liberals think of when they hear “Quaker” or talk about “silent meeting”) has a basic assumption that those who speak in worship are immediately inspired by the Spirit (God/Holy Spirit/Light Within; terminology varies). So, no previous determination that one will speak. This is still mostly observed in weekly meetings for worship that are based in silent waiting. But it is not the practice in meetings (or, as many of them are called, Friends churches) that employ a pastor, and many larger gatherings of Quakers have invited speakers who are at the very least expected to speak and frequently have announced their topic and may read from a prepared text.

Third, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, to which I belonged when I lived in the area, has a large staff, but staff members do not have theological authority. (One might say that few Quakers in Philadelphia recognize *anyone* as having theological authority, but that’s another essay.) They do of course exercise authority and leadership, but they are hired, not called, and they are subject to the direction of the hiring body. Another kind of leadership, selected by the body and serving it in a volunteer capacity, is the clerk, who is the person who moderates meetings for business. This person also doesn’t have authority within worship, per se, but does wield a considerable amount of power and is often the public face of the yearly meeting.

Third and a half, the yearly meeting is called a yearly meeting because it has annual sessions to conduct business. There is a clerk of the yearly meeting. There is also, often, a body that may be appointed or may be representative, which meets between the annual sessions of yearly meeting and conducts business on its behalf. This body also has a clerk, which in Philadelphia Yearly Meeting is a different person than the clerk of yearly meeting.

Now, on to the story. I was at the time clerk of Interim Meeting, the continuing body of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (thus, with the clerk of yearly meeting and the general secretary, one of the three most visible leaders). And I was invited by a friend to attend the weekly meeting for worship at the Friends school where she taught, with the expectation that I would speak. I was also invited to attend the spiritual life club (or some such name) at lunch, and to speak to her religion class in the afternoon.

Some Quakers of my acquaintance were mildly shocked that someone would be invited to speak in a meeting for worship, even if it was in a school. But people need to learn how to be in meeting, and Friends school administrators often feel that it is good for [non-Quaker] students to be exposed to the thoughts, concerns, and religious feelings of Quakers. So, I went and spoke and have absolutely no recollection of what it was I said. I think I quoted a scripture passage and did some interpretation.

The lunch meeting and class were very enjoyable. The students were engaged and interesting. During the lunch meeting, however, I found out that some students had been withdrawn by their parents from the meeting because I was gay. Turns out, there were conservative Christian parents in the area who did not do enough research about what Quakers in Philadelphia actually believe today. They just knew that there were these old, prestigious religious schools (they’re thick on the ground around Philadelphia), and assumed their children would have “safe” educations there.

There was a formal complaint to the school. I was, of course, a perfectly respectable choice within the context of the Quaker community of Philadelphia, and I knew this, so I was unconcerned about the kerfuffle on my behalf, but I worried about the effects for my friend and the school itself. (I mean, private schools depend upon serving a constituency that pays them.) There were meetings of the concerned parents with my friend and other administrators, and the school politely and firmly stood behind the invitation.

Wasn’t that anticlimactic? But let it be a lesson to you: don’t assume Quakers are like that quaint man on the box of oatmeal, because he’s long, long dead. Not to mention that he’s a marketing device created by non-Quakers.

Personal conversations with Evangelical and African Quakers

I’ve had personal conversations with Evangelical and African Quakers about being gay.

There really is nothing like meeting people one-on-one while working on a shared project. For many years I was part of Quakers Uniting in Publications (QUIP), which brought together Friends from across the theological spectrum who shared a concern for the printed word. In annual meetings, shared projects, and correspondence, I had occasion to get to know Evangelical, Conservative, and Friends United Meeting Quakers. I haven’t been an active Quaker in over a decade, but I still have fond memories of these individuals.

Through both work and volunteer leadership positions, I’ve attended triennial meetings of Friends United Meeting twice (in Greensboro, NC, in 1987 and Indianapolis, IN, in 1996), a World Gathering of Friends (in Elspeet, Netherlands, in 1991), and the triennial of Friends World Committee for Consultation once (in Birmingham, UK, in 1997). In each of these meetings, to some degree, I have had the privilege of getting to know people quite different from myself in small groups. Several times I was also able, with the support of other Friends, to hold worship or discussion sessions on gay and lesbian concerns. In all of these meetings, I was not the first openly gay or lesbian person to participate. But in each case, I may have been the first openly gay person some of these Friends engaged in conversation. And I loved the conversations and the people I met.

One aspect of coming forward as an openly gay person and requesting time and space is the opportunity it gave straight Friends to be supportive.

At the time this activity didn’t seem a burden, but eventually I wasn’t able to continue doing it. In a Quaker context, I might say that I did it with love and joy when it was a ministry or calling, and when the calling left I could not continue under my own power.

Hospice work and traveling in the Quaker ministry

I’ve supported people doing hospice work and traveled in the Quaker ministry with a concern to get Friends to talk about AIDS.

One aspect of the height of the AIDS epidemic was how many people were estranged from their families. So, if they were going to have help in their sickness and dying, it meant that their friends (and all too often, strangers) had to step up. I was not some Florence Nightingale, but rubbing hand lotion on a friend’s feet to soothe the neuropathy, or making sure they have a hot meal, or sitting in the hospital as they sleep, or keeping vigil on their deathbed really changes a person.

In 1992 I helped create an AIDS Working Group in Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends. Responding to a proposal from Carolyn Schodt, we created a Quaker Ministry to Persons with AIDS, which trained volunteers and paired them with people with AIDS for weekly visits. Usually the partners were people in hospice, and volunteers formed friendships, gave support, and provided respite to caregivers. I was involved in the training program and in a monthly support group for the volunteers.

My religious work among Quakers around AIDS had begun earlier, when I shared with my monthly meeting my concern that Quakers should be talking about the epidemic and considering what, if anything, God was calling them to do in response. After a discernment process, I was given what’s colloquially called a “travel minute,” which is an official statement of a Quaker body endorsing the activities of a specific Friend on a specific topic. Initially I travelled to other monthly meetings in Philadelphia Quarterly Meeting (roughly the city of Philadelphia) and later to other meetings in Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. By the time the AIDS Working Group had formed, I also travelled to other yearly meetings in North America.

Quaker practice varies widely (as does Quaker theology), and one striking memory I have is visiting Iowa Yearly Meeting Conservative. The “conservative” in their name refers to largely to practices of worship and to some degree cultural practices. Certainly the way they conducted their meetings for business was an eye-opener. When my travel minute was presented and read, upon acceptance of the minute, it was clear that Friends were prepared to hear whatever message I had, right then, should I have one. I was so used to very carefully and heavily scheduled agendas that I almost missed the significance of the moment.

My work around AIDS is part of what led me to enter a yearlong program, “On Being a Spiritual Nurturer,” led by three Friends who had created an organization called School of the Spirit. In monthly residential weekends, participants heard from a variety of spiritual nurturers from different traditions, experienced various contemplative practices, and reflected together on what we were learning. Between times we did lots of reading and reflection papers, practiced local ministry under the care of oversight committees, and considered our own particular calls to ministry.

What I learned in the School of the Spirit has informed my approach to friendships and care and support for others, although I did not formally become a spiritual director. As I’ve been taking a fresh look at my life around the occasion of turning 60, I’ve given consideration to renewing and deepening my own spiritual practice and to the possibility of offering spiritual direction to others.

The first safer-sex pamphlet in San Francisco

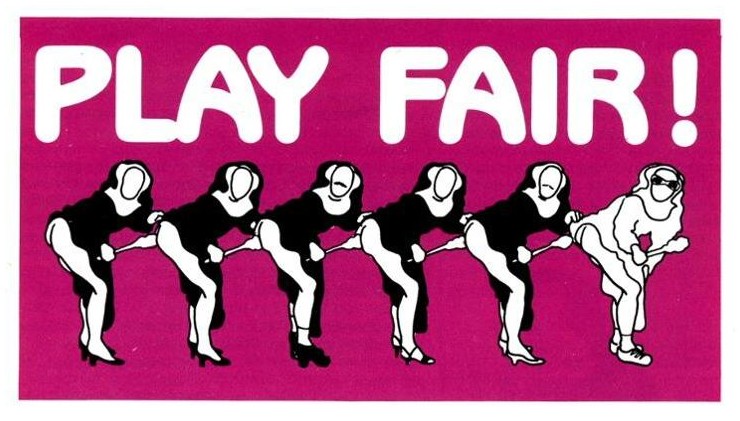

I helped support the production of the first safer-sex pamphlet in San Francisco as part of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. I grew up in a nonreligious and nonspiritual home, but while in college began exploring personal spirituality. This led eventually to becoming a gay male nun and to meeting SPI sisters. When I moved to San Francisco, I joined the order and was involved until not too long before I moved away.

The early history of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence (before my time) included protesting nuclear power in the wake of Three Mile Island and fundraising for gay refugees from the Mariel boatlift. While I was a member we raised money to produce Play Fair! as well as continuing to do benefit fundraising in the community. We were involved in antiwar protests against US involvement in Central America and rarely missed an opportunity to subvert archetypes with a goal of releasing people from shame and guilt and “promulgating universal joy.” Some of us were involved in gatherings of the radical faeries.

Today the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence around the world include members of all genders, but at that time in San Francisco it was all men. And today most members wear “white face,” a practice I disliked back then when only a few did it and dislike even more today. Some sisters, when they put on the habit (and makeup), became larger than life and bloomed into wonderfully strange flowers. A few of us became more focused and contained. The reasons for becoming nuns were individual to each, but I felt there were three major elements reflected in varying degrees by each of us: drag, politics, and spirituality.

My interest in drag has always been minimal (and it’s all drag: we’re born naked), but critical engagement with politics and spirituality continue to be important to me.

I’ve accompanied some friends who’ve died and grieved many more

Anyone who has reached the age of 60 has assuredly experienced the death of loved ones and a variety of griefs. And so of course there are people who stand out in my memory whom I remember with love.

My friend Ruth Fansler, a member of my Quaker meeting in Philadelphia and a coworker, proved to be an unexpected mother figure. She dressed for comfort, not according to any standards of femininity. She was, when I knew her, a bookkeeper, with exactly the insightful and critical curiosity that suggests. She wasn’t verbose or cuddly. We didn’t know each other all that well. And yet when I received emotional news at work one day when my father was in the hospital, I still would swear she leapt over her desk to come stand beside me and put her hand on my shoulder, because she thought the news was that he had died. When Ruth was comatose shortly before her death, members of our meeting were visiting her and singing to her. One of her sons and his family had arrived, and the other was on his way. I still remember how the heart monitors changed when her son walked into the room, even though she was otherwise unresponsive.

Anyone who knows me at all well soon learns about my great friend Barbara Hirshkowitz, who died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 57 in 2007. (Only as I write this I do realize I’m older than she was at her death.) I wrote a whole post about her (and preached once about what she taught me.)

But again, the larger context of my original statement was Coming Out Day, and there are particular points to be made about death from my perspective as a 60-year-old gay man. I haven’t just had loved ones and family members die over the course of the years, as everyone does. I came of age in Northern California as the AIDS epidemic began to spread. I lived in San Francisco from 1982–1985. Before I was 25, I had a former housemate die from AIDS, and many more friends and loved ones followed. My story is not in the least unusual. Or, if it is unusual, it is in not having had more friends and loved ones die.

One of the primary lessons I learned as a young man was people die. Not at some abstract time in the future, not some abstract people over there, not abstract groups of people. People die. People just like me. People just like me die, every day.

Redacted

“I’ve loved men deeply and only a couple of times come to regret being involved with them.” I’m sure readers will understand that I’m not going to make a public post about this kind of thing, beyond saying that unfortunately I do regret a couple of my relationships, for reasons having to do both with me and with the other party.